“I’m going to tell the John Oliver story,” Jill Ward, Director of the Center for Youth Policy and Law and Adjunct Professor said, “so just bear with me.”

Ward detailed how several of her student policy fellows were part of a project of the National Youth Justice Network (NYJN), in conjunction with students at Georgetown Law, to document the minimum age at which children across the country can be subject to juvenile court in each state. NYJN incorporated the research done by the law students into a policy brief on the issue leading to a research attribution at the end of the document. As a result of that work being acknowledged, last month Ward fielded a phone call from Oliver’s production team asking if that map was up to date and other questions related to the issue both in Maine and nationally.

It’s a fun story, but it also signifies something more about the work of the Center and Maine Law’s Youth Justice Clinic.

“It shows that we are engaged in the national conversation about youth justice and where the field is going,” Ward said. “We are well-positioned to participate in these policy and practice conversations and the most exciting part is that students are at the table learning and contributing as well.”

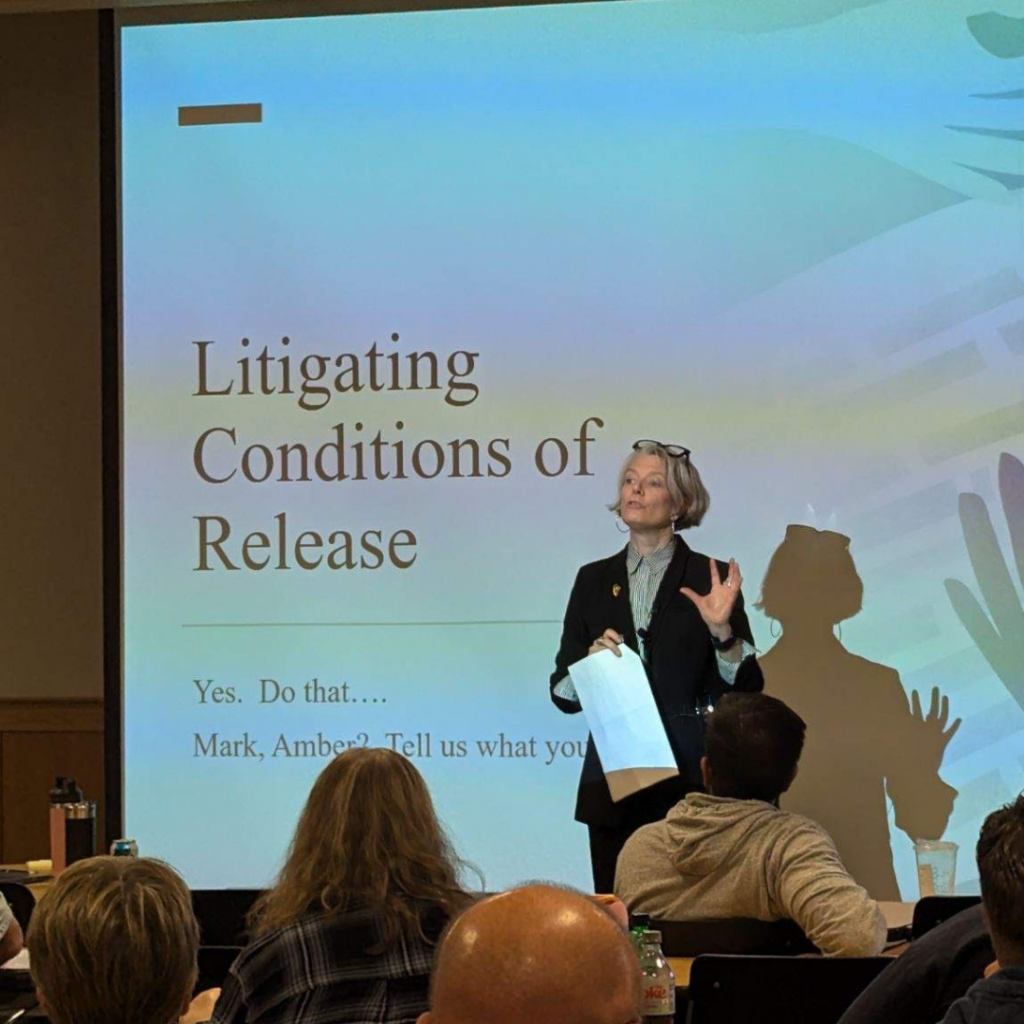

Recently, Ward, Professor Sarah Branch, Director of the Youth Justice Clinic, and Professor Emeritus Chris Northrop, Director of the Rural Practice Clinic, were asked by the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services to help organize a day during their annual conference around juvenile justice issues. Held on October 25 at the University of Southern Maine Lewiston/Auburn campus, the day brought together roughly 60 public defenders from across the state and other stakeholders.

“For us, this was a great opportunity to train youth lawyers, share best practices in the field, solidify community, and touch on some of the hot-button issues in the state,” Branch said. “Ultimately, we shared the aspirational vision for youth justice and then how defenders can put this into practice.”

At hand were a variety of topics, including how to manage school-based offenses, how to navigate the constitutional principles of defense work with the realities of representing a minor, and the issue of prohibition reform for youth.

One challenging aspect of improving youth justice outcomes for children in the state, Ward explained, is Maine has a low crime rate overall, a low youth crime rate, and comparatively good diversion rates. For that reason, many feel that the approach to youth justice in the state is “good enough.”

“We don’t want to overstate the situation when it’s not what the data reflect,” she added. “At the same time, that does not mean we shouldn’t be trying to improve in areas we know we can do better.”

Taking advantage of opportunities like the recent training helps to ensure the youth justice policy in the state reflects evidence-based programs, best practices, the science on adolescent development and reliable data. This applies not just to how defenders work with their clients but how the state treats youth in the criminal justice system. It is all part of a holistic approach the center and clinic take to ensure the best outcomes for youth statewide.

“We want to make sure we are supporting and lifting up people working in this field while also adhering to our commitments under the Sixth Amendment,” Branch said. “Coordination across sectors is key to the success of Maine’s youth and their families. Whether in the legislature or in training sessions or through our direct representation we will work to continue to facilitate the necessary collaborations and conversations.”