Since Maine Law launched the Rural Lawyer Project in 2017, the program has provided 2L and 3L students hands-on experience in rural legal practice by pairing them with lawyers who serve as mentors. The initial pilot funding for these fellowships was provided by the Maine Justice Foundation, with continued support provided by a three year Betterment Fund Grant.

Since Maine Law launched the Rural Lawyer Project in 2017, the program has provided 2L and 3L students hands-on experience in rural legal practice by pairing them with lawyers who serve as mentors. The initial pilot funding for these fellowships was provided by the Maine Justice Foundation, with continued support provided by a three year Betterment Fund Grant.

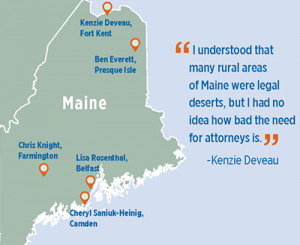

In addition to the usual challenges of spending a summer working in busy general practice law firms, 2020’s cohort of Rural Law Fellows also faced singular complications presented by the COVID-19 crisis. “The biggest difference was the ‘new normal’ of client meetings and communications happening primarily by phone, video, or even outdoors,” says 3L Cheryl Saniuk-Heinig, who returned to the familiarity of Camden Law LLP in Camden in the unfamiliar context of a global pandemic.

A more positive difference Saniuk-Heinig experienced as a second-year fellow was the opportunity to work on projects she describes as “more tailored to both what I was interested in learning and sought more practice with.” 3L Ben Everett, who returned to Swanson Law, P.A. in Presque Isle, had stayed in touch with the firm throughout the school year and was able to “see several cases through from start to finish.” Having another year of law school under his belt also allowed him to “bring more substance” to his client interactions.

For 2L Chris Knight, whose fellowship took him to Sanders & Hanstein in Farmington, the pandemic provided one major letdown: “I was disappointed not to have the opportunity to work on or observe any jury trials,” he says. Despite this blow, Knight says that “the program gave me the opportunity to experience practicing rural law while also receiving a highly immersive, hands-on experience. I was really able to engage with a huge variety of legal issues and projects.”

At The Sutherland Law Firm, LLC in Belfast, 2L Lisa Rosenthal was mentored by an attorney whose solo practice includes court-appointed Guardian ad Litem and child protection work, family law, and civil litigation. Rosenthal says, “It was emotionally challenging to meet the playful children in person or on video, and then read about the physical and emotional abuse they’ve experienced, usually as a result of addiction and untreated mental health issues in their families.” The experience made her decide to serve as a Guardian ad Litem, no matter what type of law she ultimately decides to practice.

2L Kenzie Deveau, who grew up in northern Maine, worked at the Law Office of Toby Jandreau, P.A. in Fort Kent. “I understood that many rural areas of Maine were legal deserts,” she says, “but I had no idea how bad the need for attorneys is.” She was also surprised by how much work is available to new lawyers in Aroostook County. “A new attorney in southern Maine typically takes any case they can get, but in northern Maine they could go to the court clerk and be presented with a stack of cases to pick from.”

Deveau was also impressed by the judiciary’s response to the pandemic: “We were able to have quick and simple pre-trial and dispositional conferences right from the office, without travel time or time waiting at the courthouse. In a rural area that makes a world of difference.”

Several of the Fellows praise the ability of these rural law firms to quickly adjust to client needs in difficult circumstances. They’re equally enthusiastic about the Rural Lawyer Project itself. Rosenthal says, “Working for a small practice in a small town enabled me to dive right in and hit the ground running. When I was choosing which law school to attend, a trusted advisor asked me, ‘Do you want to represent people or corporations?’ When I answered, ‘People,’ he advised me to seek experiences that gave me direct client contact – the Rural Lawyer Fellowship has done exactly that.”

The Rural Lawyer Project is the result of a collaboration among the Law School, the Maine Justice Foundation, the Maine State Bar Association, and the Maine Board of Overseers of the Bar.