By Associate Professor Anthony Moffa

If you are reading this, you have probably heard the mantra “work smarter, not harder” at some point. Attributed to engineer Allen F. Morgenstern and coined in the 1930s, the message is simple, yet powerful – more effort, hours, pages does not always yield better results.

If you are reading this, you have probably heard the mantra “work smarter, not harder” at some point. Attributed to engineer Allen F. Morgenstern and coined in the 1930s, the message is simple, yet powerful – more effort, hours, pages does not always yield better results.

Whether you are a law student approaching exams with an appropriate sense of dread or an agency attorney in the new federal administration staring down the daunting task of modernizing the regulatory state to confront unprecedented environmental and health crises, it probably wouldn’t hurt for you to hear it again.

While I have only anecdotal data from reading (and grading) exams to counsel students, I have a wealth of data from the Federal Register, reported cases, and public comments to counsel regulators. Over the past three years, I have analyzed that data and presented my findings in a series of two articles published in the Nevada Law Journal.

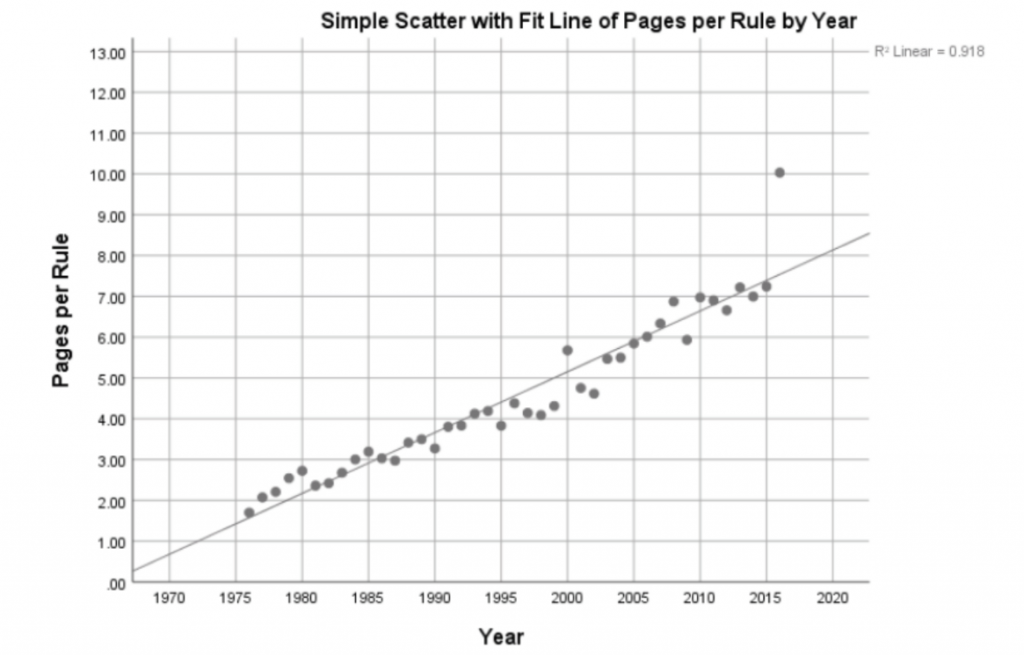

The story begins with a relatively straightforward, documented trend – over the past 50 years, the average length of Federal Register entry for each new rule has steadily increased. Just look at the graph below.

My work sought out to explain why. And also to examine whether any of those explanations made logical sense. The bad news first. Making a rule’s Federal Register entry longer has not historically resulted in that rule being more likely to survive judicial review, even if one just looks at the part of the entry that seeks to legally justify the rule (i.e. the preamble). Changes in those preamble sections have, not coincidentally, contributed to the overall increase in rule length over time, despite the lack of any empirical evidence that more content in them helped when a rule was challenged in court.

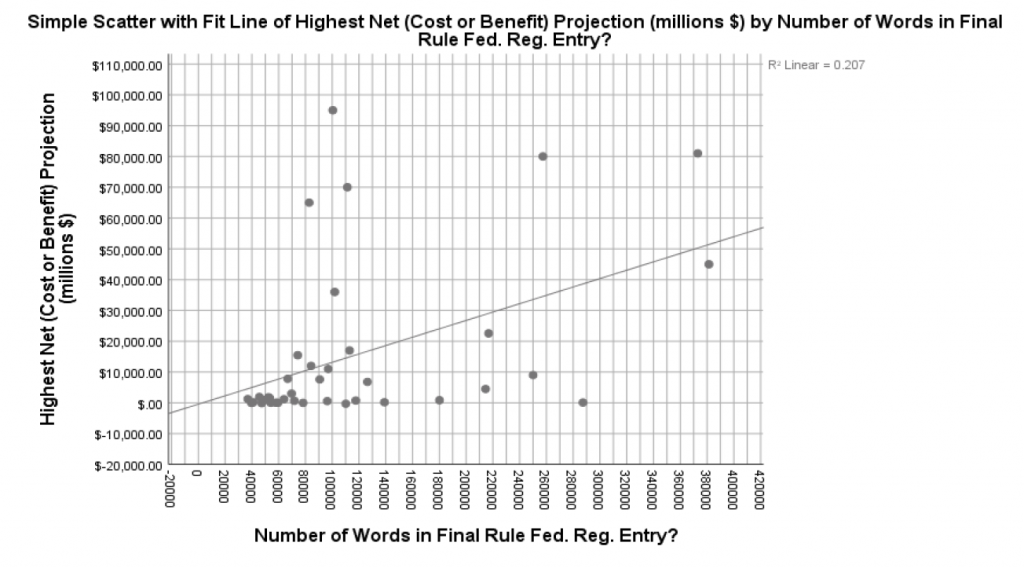

Now for the good news. Longer rules have historically produced more net benefits to society.

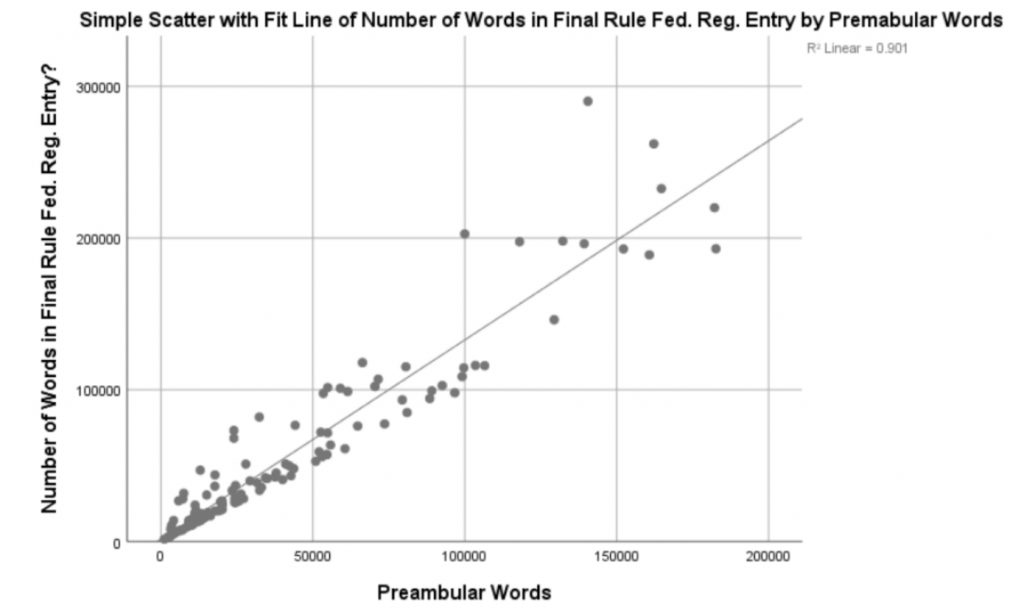

Lastly, the news that begs for more analysis. The more public commentary on a rulemaking, the more words have been needed to ultimately promulgate the rule.

All of this suggests that writing more has both costs and benefits. Regulators, and students, should be intentional, and data-informed, when making decisions about how to allocate writing resources (aka words and pages).

The full articles from which this discussion emanates can be found on my SSRN page.