A few years ago, before the onset of a global pandemic, I noticed that my preferred Portland, ME coffee shop – Tandem Coffee Roasters – implemented a new policy. Upon ordering a beverage, the barista asked if I brought my own mug. They informed me that, if had I not, I could purchase a paper, disposable vessel from the shop for twenty-five cents. Some might (understandably) ask, “Does coffee not come in a cup anymore?”

My mind instead went immediately to behavioral economics, specifically, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s famous theory of “nudges.” Ultimately, I decided to write about this idea, producing an article that is now forthcoming in the 2022 volume of the Dickinson Law Review.

The shop implemented what I call a “private environmental nudge,” a subset of policies that define private environmental governance – the actions taken by non-governmental entities to achieve traditional governmental ends regarding environmental protection. Here, Tandem incentivizes the use of reusable cups, thereby reducing the waste created by single-use cups. Their “nudge” involves lowering all posted drink prices by twenty-five cents and charging twenty-five cents to any customer needing a single-use cup. In other words, they created a private environmental tax in lieu of a private environmental subsidy. The economics for the business are identical to the more common nominal discount for bringing a reusable cup; the only difference is in choice architecture.

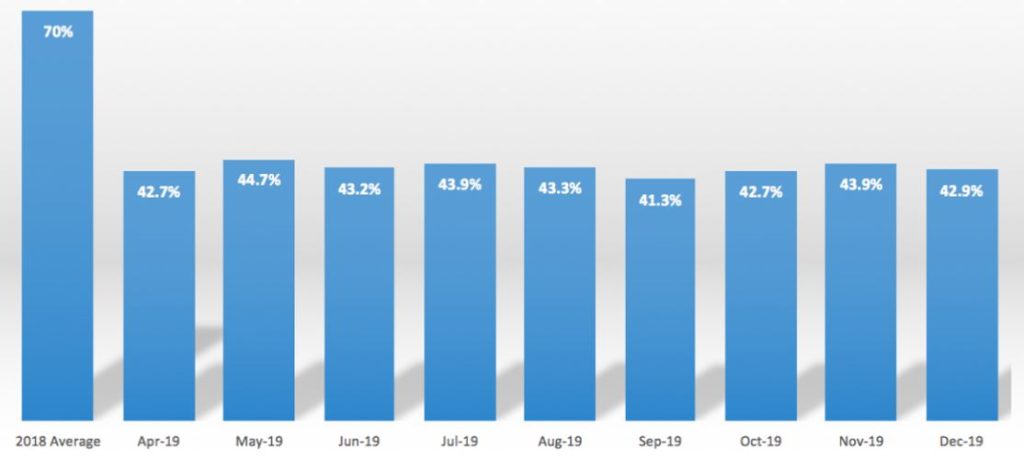

Customers have grown accustomed to seeing small discounts for use of reusable products. Grocery stores, such as Whole Foods, for example, discount five or ten cents per reusable bag. The pertinent question is whether re-framing the choice, making environmental responsibility the default ( i.e. providing their own receptacle), and charging a penalty to those who act less responsibly, proved an effective tool of private environmental governance. Thaler and Sunstein’s insights on loss aversion, mindless choosing, and framing reinforce this theory. Tandem’s sales data also confirms this.

Percentage of Drinks Sold in Single-use Cups at Tandem Coffee Roasters 2018-19

Now, as we emerge from the pandemic, other local shops (and eventually even Starbucks) are implementing similar policies. This story illustrates how small, locally-owned businesses, particularly in the food service sector, can contribute positively to private environmental governance,, They can be valuable role players not only by reducing their own waste and life-cycle emissions but also by influencing policy development and norms.

I sat down with Will Pratt, one of the founders of Tandem, to discuss the policy, my paper, and the future of private environmental nudging for his and other small businesses.

Will explained, “It all started with everyone trying to get rid of straws. What’s the next thing that we can work on getting rid of? And so, we were like, let’s change the way we talk about cups.”

Asked about the two nudges involved – the default switch and the nominal fee – Will believes the default switch primarily drove the observed change in behavior seen in the chart. Will based the policy not on academic research, but on instinct, describing “the guilt that I was feeling at the grocery store” when asked if he needed a bag and he had forgotten to bring one. Will went so far as to say, “ It’s not the losing 25 cents. It’s just the fact that you have to think about it. . . .That number could have been anything.”

We discussed how the next nudge might look. Will reported that Blue Bottle Coffee, a major player in the national coffee scene, stood poised to switch the default milk for their beverages from dairy to oat (oat milk is significantly less carbon intensive and poses no animal treatment issues). From that story came the seed of a new idea based on something I wrote about in the paper. Maybe even just changing what we call the milk options could have an effect. As Will put it, “It’d be so awesome to put ‘cow’ on the menu. Right? Like ‘cows milk.’ When you start to think about it, it’s gross. . . . ‘We have this stuff that nourishes baby cows, I don’t know what it does to you.’”

I don’t know if the next innovative private environmental nudge to come about will change the way you order a latte. What I do know is that I, and potentially big business will be watching our local coffee shops closely.